A person goes to a fancy restaurant and finds the menu has no prices listed. The person wonders whether he can afford to eat there. The answer is "If you have to ask, you cannot afford it."

My experience has been that head shape is a very unreliable identification characteristic. With training and experience, a person can identify many venomous species based upon head shape. However, most persons do not have such training and experience. Like the restaurant customer, if one has to rely upon head shape for identification, one cannot make an accurate identification.

Most venomous snakes in the United States are pit vipers. Pit vipers have large, wide heads and narrow necks. They also have bulging venom glands on top of each side of their head. This shape is often referred to as an "arrowhead" shape. Some of our nonvenomous snake species have large heads and narrow necks. The term "arrowhead" shape is not precise. I have found many Native American arrow and spear points in my life. Their shapes range from triangles to ovals. I expect I could match a point's shape for every snake species' head shape. The situation is further complicated by the fact that many nonvenomous snake species change the shape of their heads when in a defensive posture. They do this by flattening their heads to make them wider. Large species such as water snakes and small species like Brown Snakes do this. Here are pictures of a Cottonmouth (venomous) and a Banded Watersnake (nonvenomous). Which has the most arrowhead-shaped head?

Return to Snake Questions

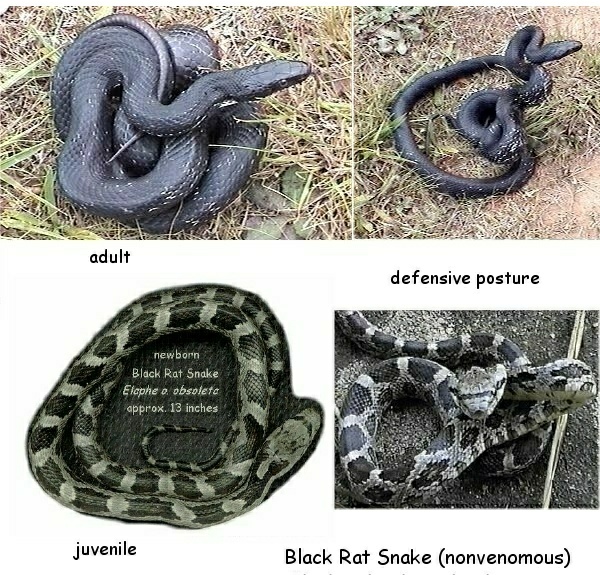

By far, the snake species that is most often found in houses and buildings is the Black Rat Snake (Elaphe obsoleta obsoleta). Black Rat Snakes are large nonvenomous snakes which eat rats, mice, squirrels and birds. Black Rat Snakes and its subspecies (Yellow, Gray, Everglades, and Texas) are found throughout the eastern half of the United States. In South Carolina, they are an abundant species.

There are three reasons why Black Rat Snakes get in homes and buildings so often. First, they are abundant. Second, their principal prey, rodents and birds, thrive around our homes and buildings. And third, they are excellent climbers. Black Rat Snakes hunt by scent and sight. They can follow the trail of a mouse or squirrel along its secret path into our homes, no matter whether the trail leads through the crawlspace or the attic.

Adult Black Rat Snakes have shiny, jet black backs and show very little pattern. Yellow Rat Snake backs are yellow/olive and show 4 dark stripes; Everglades Rat Snakes are similar but have an orange background color. Gray and Texas Rat Snakes are heavily blotched. Juveniles of all subspecies are blotched.

Rat Snakes will attempt to remain unseen by freezing in place when first threatened. This strategy leads to many of them being killed on our roads. However, even newborns will assume a striking defensive posture when cornered and harassed. They will bite and adults can puncture the skin. They will also emit a strong musk smell.

Return to Snake Questions

I am not the best source for information about keeping snakes away. I have always sought them and never tired to keep them away. Thus I have not tried any of the folk methods for repelling snakes, nor any of the commercial products offered for such purposes. However, in searching for snakes I look for environments which attract snakes. It follows that lowering the attractiveness of a yard to snakes is a method of repelling snakes. Therefore, I can describe some environmental factors which attract snakes and you may wish to avoid or reduce them your yard. However, you may find that many features that you find attractive in your yard are also attractive to snakes. Everything is a balance between benefits and costs. Personally, I think it would be much better for you to learn to share your yard with snakes, just as you do with other native wildlife.

Snakes can be discouraged from a location by less food, reduced shelter, and more predators. They can also be diverted using physical barriers.

Food: All snakes are carnivores, that is, they eat other animals. Larger native snake species which often enter our yards eat rodents, birds, lizards, and smaller snakes. Each of these prey have adapted well to living with humans. They make their homes in the trees, scrubs, and flower beds we cultivate in our yards. Squirrels, rats and mice often live in our homes and buildings. We put out feeders to attract birds and squirrels. The more prey animals we invite into our yards, the more snakes will be attracted.

Shelter: Due to the nature of their physiques, snakes are very vulnerable creatures. Very few of our native snakes can successfully thwart an attack by a cat or dog. Their best defense is to be cryptic or unseen. Availability of shelter is the key to this defense. The more places to hide, the more attractive your yard will be to snakes. A snake will cross an open area of yard with much reluctance. Leaf litter, tall grass, weeds, vines and scrubs provide cover for snakes while moving. When not moving, they prefer to hide beneath something. Boards, trash, and yard objects provide cover for snakes. A broad border of well-trimmed lawn is a great discouragement to a snake.

Predators: Dogs and cats are major predators of snakes in suburban areas. Most dogs will attack and kill even our larger species. Domestic cats are particularly effective in reducing snake populations. Yard cats kill many small snakes. They also kill many birds, mice, and lizards which might otherwise be food for snakes. Yard fowl, such as chickens, turkeys, and guinea hens, are also predators of small snakes.

Physical barriers can also be useful in repelling snakes. Although it is very difficult to make a fence which will absolutely prevent a snake from crossing, fence-like barriers can be used to guide snakes away from your yard. For example, rock wall can be traversed by many snakes. However, if the wall is free of scrubs and vines, the snake will be fully exposed to predators while on the wall and thus will be reluctant to cross. The wall then functions as a barrier which directs the snake along its length. Strategically placed, such a wall can divert snakes away from your yard.

Return to Snake Questions

Persons moving to South Carolina, especially those from the more urban or more northern states, are often concerned about having dangerous encounters with snakes. In movies set in the South, venomous snakes are always lurking in hidden places to attack unsuspecting heroines. Friends and neighbors love to tell about their close encounters of the snakey kind.

The truth is there are more snakes in southern states than the northern states. Reptiles prefer warmer climates. There are more snakes in rural states than urban states. Urban environments destroy habitats and urban activities kill creatures. So you are more likely to encounter a snake in South Carolina than where you are coming from.

What you need to know is that an encounter with a snake does not have to be a bad experience. Snakes have small brains that are not capable of the bad attitudes that we humans are. Snakes react in predictable ways. When a snake encounters a human, its overwhelming goal is to avoid being killed. It will not be out to get us. All our native snake species are small animals compared to humans. Snakes do not see us as prey, only as danger.

A snake's first action is to keep from being seen. We humans interpret this as being "sneaky," but it is really a very effective defense. Even the venomous snakes employ this defensive behavior. In a direct confrontation with a human, a snake will lose. So even the most venomous of our snakes will let you pass by rather than call attention to itself. This is not smart behavior, but very effective evolved behavior.

The second line of defense for our snakes is to try to escape. Some of our snakes can crawl very fast and some are much slower. The faster the snake can move, the more readily the snake abandons the stealth defense for the flee defense. Another factor that encourages the flee defense is close proximity to cover to hide in. A snake can disappear very quickly in thick ground cover, or under water if the snake is a semi-aquatic species.

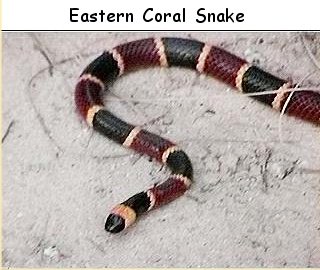

Some of our venomous species have a different secondary line of defense, that of warning that they are truly dangerous because of their venom. The snakes that can use this defense are the large rattlesnakes, the Cottonmouth snake, and the Coral Snake. The rattlesnakes can produce an audible rattling sound. The Cottonmouth puts on an elaborate display of opening its mouth very wide and holding it open. These snakes are heavy-bodied and can not effect a good flee defense. The Coral Snake advertises its dangerous nature through its bold colors. We have some nonvenomous species that are colored similarly, but not exactly the same, as the Coral Snake presumably to mimic the Coral.

The last line of defense for snakes is the active defense. This is when the snake will actually bite to defend itself. Even in this stage of defense, many snakes, including venomous ones, will try to make themselves more threatening looking in the chance they can frighten the attacker away. The Diamondback Rattlesnake raises its head and fore body off the ground in a classic "S"-shaped curve. The nonvenomous Black Rat Snake will also assume this posture. Many nonvenomous snakes flatten their head and body. This makes them look larger. It also makes the head look more like the head of a venomous snake.

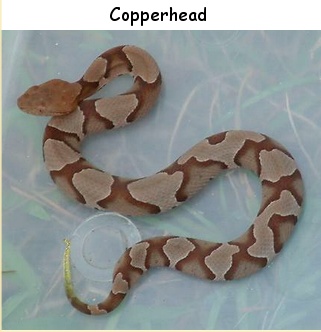

Snakes use the biting defense when they are physically assaulted, such as being stepped upon, grasped, or hit, or perceive they are trapped and have no other defense. It has been reported that the Copperhead is our venomous species that will most readily resort to biting. Their flee defense is not good and they have no warning defense. Copperheads are superbly camouflaged. In dry leaves, they can be almost impossible to see. They rely almost exclusively upon the stealth defense. When they perceive danger, they will freeze in place. In natural habitat, this defense works very well. They do not calculate whether they are in a location that is suitable for effective camouflage. They will even freeze in place on a road or sidewalk where they stand out to all who look. However, most people still overlook them because they are not moving and are perceived to be a stick. On roadways, this behavior very frequently results in their deaths from vehicles.

In South Carolina you are far more likely to encounter a nonvenomous snake than a venomous one. Our nonvenomous snakes are no danger to humans, except in the case of our causing injury to our self or others through irrational behavior. One would think that it would be helpful for newcomers to be able to recognized the venomous species. However, most native Carolinians cannot distinguish venomous species from the nonvenomous species. But let's give it a try anyway.

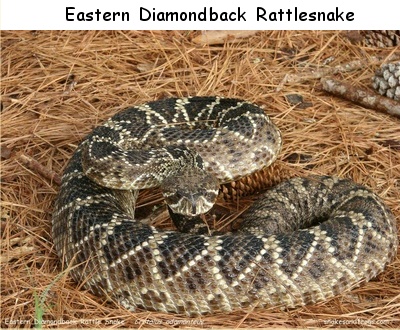

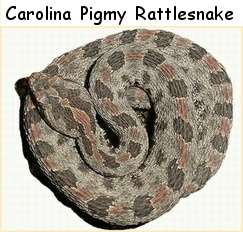

We have six species of venomous snakes native to the state. Two of the venomous species are the large rattlesnakes, the Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake and the Timber Rattlesnake. Theses snakes can be recognized as venomous by the rattles on the ends of their tails. Rattles will break off sometimes, but adults usually have some rattles. Very young snakes may not have rattles that are noticeable. Many snake species, venomous and nonvenomous, vibrate their tails when nervous. In dry leaves, this vibration can produce audible rattling sounds. Simply seeing a snake shake its tail is not sufficient to determine that it is venomous. A third venomous specie is also a rattlesnake, the Pigmy Rattlesnake. Pigmies are small, seldom growing more than 20 inches long. Their rattles are small, even on adults. In the pictures of the rattlesnakes below note the bold diamond pattern that gives the Diamondback its name. The Timber Rattle has dark, chevron shaped bars down the length of its back. Timbers can also have a reddish stripe down the middle of the back. The Pigmy Rattlesnake has a reddish or gray background color with many dark spots.

Two other venomous species are the moccasins, the Cottonmouth and the Copperhead. The Cottonmouth is also known as the Water Moccasin because it lives in wetland habitat and is classified as a semi-aquatic species. The Copperhead is also known as the Highland Moccasin because it is a terrestrial species. The Cottonmouth is a dull colored and patterned snake. It can be difficult to distinguish the Cottonmouth from our nonvenomous watersnakes. The Copperhead is a boldly patterned and colored snake. Its colors are pale, creamy pink or orange with dark brown or reddish bands. The bands are not true bands since they do not completely encircle the girth. The Copperhead's belly is pale with many dark spots.

The rattlesnakes and the moccasins are pit vipers. They are vipers because they have long, foldable fangs in the front part of the mouth. They are pit vipers because they have special heat-sensing glands in a pit located between each nostril and eye. These snakes eat warm-blooded prey such as mice, rats, and squirrels. The heat-sensing glands allow them to detect the presence and location of prey, even in complete darkness. They may also eat cold-blooded prey such as insects, frogs and fish.

All of our pit vipers have elliptical eye pupils, like a cat's eye. None of our nonvenomous snake species have elliptical pupils; their pupils are round, like your pupil. A snake's eye pupil is not a characteristic most people notice, but if you know to look, it can be seen. Remember that in the dark, an elliptical pupil expands to the side, becoming more round. So look at the pupil in the light to determine its shape. The pit vipers also have large heads and well-differentiated necks. They also are heavy bodied.

The last venomous species found in South Carolina is the Coral Snake. Coral Snakes are very different from the pit vipers discussed above. They have small heads, slim bodies, and round eye pupils. Most Coral Snakes are less than 2 feet long. They are boldly marked and colored by bands of black, yellow, and red. Our native Coral Snakes can be distinguished from our native look-alikes by the order of the bands. If the red bands are bordered by yellow bands, the snake is a Coral. The Coral Snake eats mainly cold-blooded prey, including other snakes.

All six venomous snake species are found in the low country part of the state, that is, from the sandhills to the beaches. In the piedmont region, the Copperhead and Pigmy Rattlesnake may be found. In the high foothills and mountains, the Copperhead and Timber Rattlesnake may be found.

The venomous snake most commonly encountered is the Copperhead. The Copperhead is very adaptable to many different habitats, even in suburban areas, and can be found throughout the state. Its population is large. The Cottonmouth is also a very successful species. Its habitat is usually limited to wetlands and nearby areas. In the low country, the Timber Rattlesnake is fairly common. Timbers in the low country are also called Canebrake Rattlesnakes.

Timber Rattlesnakes probably lived throughout the state at one time. Now they appear to be absent from most of the piedmont. In the high foothills and mountains, there numbers seem to be decreasing. Pigmy Rattlesnakes tend to have spotted, localized populations. Their populations in the piedmont are very limited. The Coral Snake is strictly a low country species. The Cottonmouth does not appear to have established populations outside of the low country, although many people mistake nonvenomous watersnakes in the piedmont for Cottonmouths.

Return to Snake Questions

For identification, I rely most heavily upon:

Peterson Field Guides "Reptiles and Amphibians, Eastern/Central North America"

by Roger Conant and Joseph T. Collins,

by Houghton Mifflin Company.

For herps specific to South Carolina and neighboring states, I like:

Amphibians and Reptiles of the Carolinas and Virginia

by Bernard S. Martof, William M. Palmer, Joseph R. Bailey, and Julian R. Harrison III,

University of North Carolina Press.

Specifically for snakes there is a new book out that I like a lot:

Snakes of the Southeast

by Whit Gibbons and Mike Dorcas,

University of Georgia Press.

Return to Snake Questions